By Janne Walsted and Lars Guldager

The pressure on CEP companies to obtain the right system design

When investing in new sortation systems for today’s large, modern parcel distribution hubs, CEP operators need proof of design: they must be sure that they are investing in systems that can actually meet their business demands, as well as future operations.

So, how can a distribution hub be satisfied that a new system it is investing in can actually handle its parcel volumes and sort plans at the highest performance?

The CEP company could, of course, physically test the system and certainly, this is how testing has been performed. But physical testing poses a number of obvious problems for larger hubs:

- The bigger and more complex the system, the more onerous (or impossible) the practicalities become to physically test it.

- Physical tests are costly for the CEP company.

- Physical tests are very time-consuming – it can take many physical runs before a CEP business can be satisfied a new system is ready and able to meet its particular business requirements.

Take the logistics of physically testing whether a system can handle 60,000 parcels per hour, for example. This would involve gathering and storing 60,000 parcels, making and printing 60,000 parcel labels, marking the parcels and having trained and experienced staff to handle the parcels in order to get an accurate picture of system performance.

By using a digital twin to test a system, the hub is relieved of this enormous logistical effort, time and money.

What is a digital twin?

But what is it we’re actually talking about when we suggest using a digital twin?

A digital twin is a digital replica or digital overlay of a physical asset or operation. This digital representation or virtual model replicates the asset’s performance, allowing the creator of the digital twin to determine whether the asset — in this case, an automated sortation system — operates at high performance and where it can be improved.

The infrastructure behind a digital twin

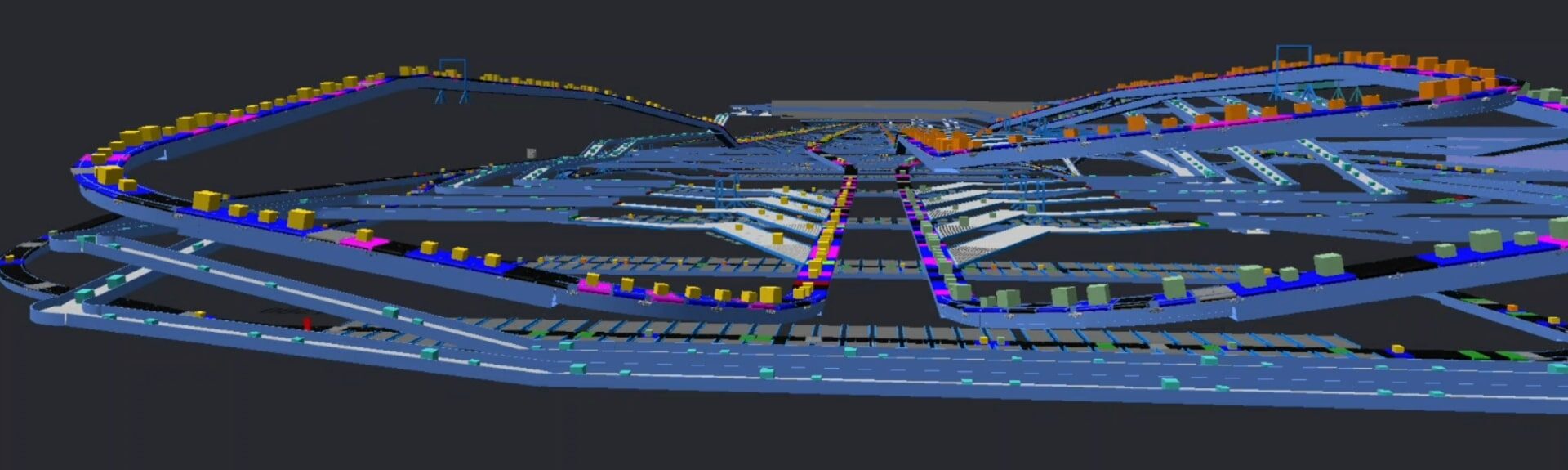

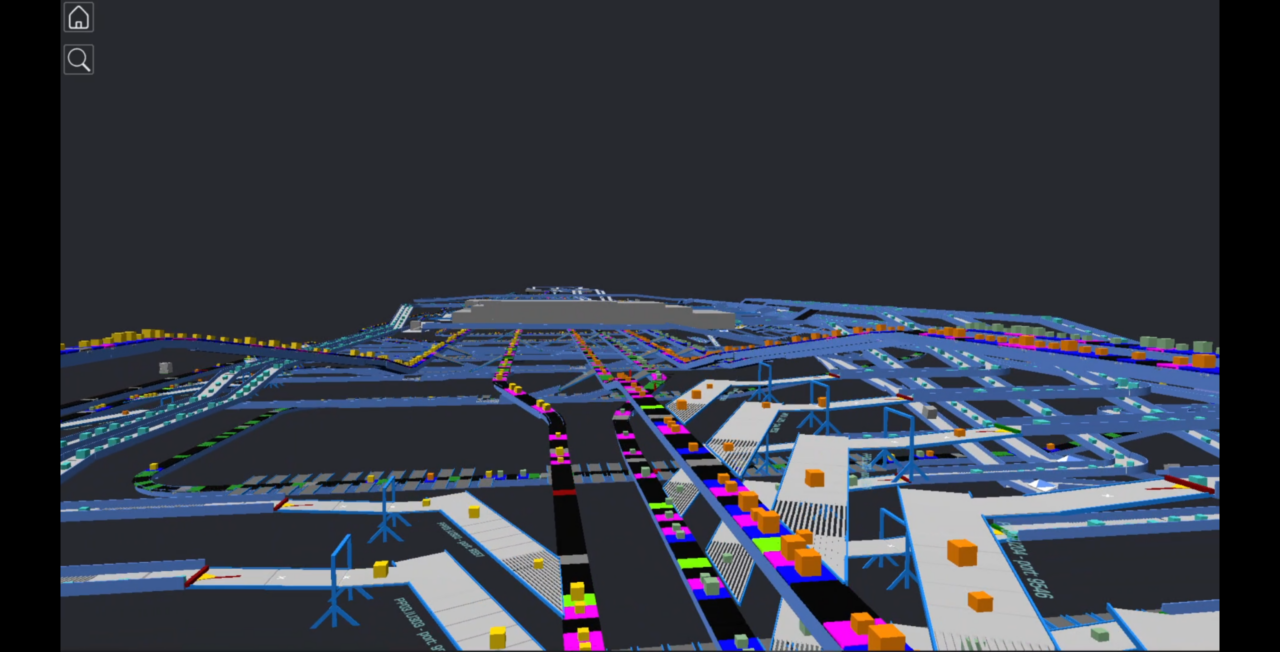

A digital twin is a combination of two components: data and a representation of the given system. The representation can be two or three-dimensional, depending on the solution provider.

Data is collected and enriched and run through highly advanced visualisation software. The data adds a visual layer on top of the representation to make information relatable for the staff operating the system.

These layers, lifted from the data, could consist of information telling the system throughput, ‘no reads’, power consumption, and mechanical and electrical status. An extremely valuable feature of the digital twin is that it can be observed through various filters. CEP professionals can observe the entirety of their sortation systems while only focussing on capacity, for example.

Digital twins as proven technology: Their use in other industries

Digital twins are not new technology – they were invented by NASA in the 1990s – and have since been applied to great effect in other industries.

Digital twins have been used for many years now in the airport industry, for example. With airport baggage handling systems being so large and complicated, some form of digital modeling that could test software before it was implemented became necessary. Many airports have successfully used the digital twin technology to test baggage throughput and capacity.

What started as a means to train and test software, however, has led to wider applications of digital models. Airport operators have been using digital twins in their daily operations to achieve greater optimisation, detection of system anomalies and predictive maintenance. And as more and more data is added, it won’t be long before digital twins will be used to test even more variables such as catering flows or the transportation of luggage containers at the airport.

How digital twins can benefit CEP companies

The experience and knowledge gained through the airport sector’s application of digital twin technology stand to really benefit the CEP industry.

Digital twins can be invaluable tools for CEP professionals to test capacity and simulate production scenarios. By observing a digital twin, they can gain an overview and a good understanding of how an actual system and its processes will function in the physical world.

Typically, a systems provider assists the distribution centre in establishing the infrastructure that collects data from the sortation system, such as PLCs or sensors. And even if the hub is a greenfield project and has yet to generate the data, it can perform its testing on computer-generated data. The provider processes the data and runs it through highly advanced visualisation software. The result is a digital twin – a version of the sortation system recreated in 3D.